by Lee Wardlaw

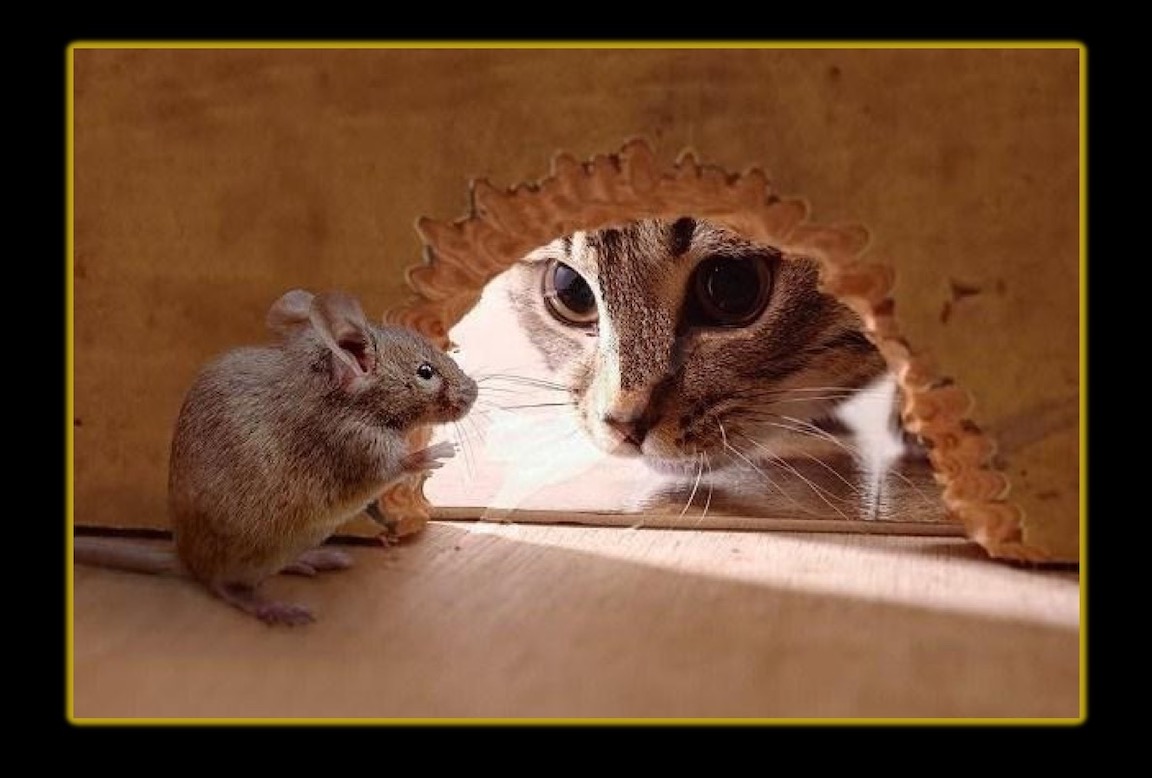

1. When poised at a hole, remain still – use your ears, eyes, nose, whiskers and mouth to detect a lurking creature.

In other words: OBSERVE

Observation is crucial to haiku. One must quiet the mind and use all five (or more!) senses to absorb, appreciate, and anchor the moment.

A dog stopped here once.

And here. There. And here again.

Oh, a cat’s nose knows!

Proper cats prefer

playthings with feathers or fur.

So whose toys are these?

Curious. This door

is NEVER closed. Perhaps YOWL

is the magic word?

2. There is no yesterday; there is no tomorrow. There is only you, scratching me under my chin right now.

The best haiku emerge from a right-this-instant experience – or from a memory of that experience. Always use present tense to heighten immediacy and authenticity in your poems.

I dub her Pinchy.

He’s – OW! – Tail-Yanker. You, Boy,

rub my chin just right.

3. Be patient. Then, when least expected – pounce!

Haiku captures a moment in time, revealing a surprise or evoking a response of a-ha! or ahhh. This pounce helps the reader awaken and experience the ordinary in an extraordinary way.

NO!

My cat is funny.

He likes to chase flies and bugs.

I love him a lot.

YES!

Pesky fly! Allow

me to muzzle his buzzle.

Never mind the lamp.

4. Most cats have 18 toes – unless we’re polydactyl; then we might have 20, 22, even 28 toes!

Japanese haiku feature a total of seventeen beats or sound units: five in the first line, seven in the second, five again in the third. This 5-7-5 form doesn’t apply to American haiku, however, because of differences in English phonics, vocabulary, grammar and syntax. Forcing an unnecessary adjective or adverb into a haiku simply to meet the 17-beats rule can ruin the flow, brevity, and meaning of your poem. So feel free to experiment with any pattern you prefer (ie; 2-3-2, 5-6-4, 4-7-3) – provided the structure remains two short lines separated by a longer one. Remember: what’s most important here is not syllables but the essence of a chosen moment.

Towel, brush, tub o’ suds.

Such fuss and muss

to still smell like dog!

(14)

Towel, brush, tub o’ suds.

Such a lot of fuss and muss

to still smell like dog!

(17)

5. When I’m out, I want in; when I’m in, I want out. Mostly, I want out. That’s where the rats, gophers, lizards, snakes, bugs and birds are.

Traditional haiku focus on themes of nature, and always include a kigo or ‘season’ word. This doesn’t mean you must be explicit about the weather or time of year. A sensorial hint (ie; a green leaf versus one that is russet-colored) is all that’s needed.

Crickets crunch. Mice snap.

Wing thing makes a dusty snack.

No meat on a moth!

6. What part of meow don’t you understand?

Tease a cat and it won’t bother to holler – it will bite and scratch. It shows its annoyance rather than tells. Good haiku follows suit. Instead of explaining, haiku illustrates a meaning or emotion through vivid imagery. Your poems should create a mental picture that captures the resulting feeling it evokes.

Alone, Q-curled tight.

Night is cold without you, Boy,

despite my fur coat.

7. If you refuse to play with me, I will snooze on your keyboard, flick pens off your desk, and gleefully shed into your printer.

Yes, haiku has ‘rules’, but remember to play! Use words as toys, and frolic with them in new ways to portray images, emotions, themes, conflicts and character.

Hey, Pest! Heed my hiss!

My blankie. My bowl. My boy.

Trespassers bitten.

Belly pounce. Nose lick.

Whisker-kiss. Ha! Can’t escape

furry alarm clocks

8. When in doubt, nap.

Good writing comes from revising. Set aside your poems and allow them to ‘nap’ for a few days.

Breaking news: YOU SNORE!

Twitch and whimper, too. Yet you

make a fine pillow.

Then revise them with rested eyes, alert ears and a fresh mind. And if too much rewriting causes the weary, bleary blues, well, there’s always that comfy looking couch or pile of dirty laundry:

Naptime! Be gone, O

fancy pad. I prefer these

socks. They smell like you.

Extra credit: #9.

Don’t Give Up. Practice Makes PURRRRFECT.

It’s a fine life, Boy.

Nap, play, bathe, nap, eat, repeat.

Practice makes purrfect.

The poems in this article are from WON TON – A CAT TALE TOLD IN HAIKU and WON TON AND CHOPSTICK – A CAT AND DOG TALE TOLD IN HAIKU, both written by Lee Wardlaw, illustrated by Eugene Yelchin, published by Holt Books for Young Readers.

About the Author

Lee Wardlaw is the author of 30 books for young readers including WON TON – A CAT TALE TOLD IN HAIKU (Holt), recipient of close to 50 awards and honors including the Lee Bennett Hopkins Children’s Poetry Award, the CWA Muse Medallion, and the Purina/Fancy Feast Love Story Award. Lee lives in Santa Barbara, CA with her husband, Craig, and two former shelter cats, Coconut and Bumblebee. For more info about Lee and her books, visit leewardlaw.com.

I love this, Lee. Can I say it is brilliant and fun and true? I want to have my teacher friends share it with kids to elevate their haiku attempts. I always loved helping kids to get into the essence of haiku. Loved it since I was in college studying. My program was different. I went to a Liberal Arts school waaaay back in the day, not a teachers’ college so we had a very different set of courses. (I loved that aspect, gave me the idea that I had to figure things out and be creative!) I had to create a lesson and figure out how to implement it as part of a classroom experience while only a sophomore. I found In a Spring Garden and a cat haiku book (need that title and will send, if you don’t know it, I think you’d like it) and those two books have stayed as treasures in my life. Plus while I was so green as a “teacher”, the kids did write some nice haiku. Not sure if I still have some but bet if I looked I might!!! Meeee-wow!!!!!

What a lovely response. Thank you, Janet! I’m a former teacher, too, and the first lesson I chose to teach to my fellow college students was…haiku! I used that lesson many times, later, with my young students. Would love to know the name of the cat haiku book you used. Purrs, Lee